| Related Links: | Articles in Guyana Review |

"Sash gang" saws cut blind resulting in poor recovery of volume, a circumstance that has serious implications for wastage of high grade lumber. Gang saws allow for the opening of the face of logs to detect defects and "cut around" those defects. Wastage, therefore is minimized.

When the large millers begun to refocus their attention on the local market during the 1990s they found an ample supply of cheap lumber supplied by chainsaw operators. Confronted with their own economic pressures they immediately cried "foul," complaining that the cheap supplies being offered by the chainsaw loggers was a function of the fact that they were operating illegally. The reality is different. Large operators have, over the years, been unmindful of the country's poor forest resources and at any rate the reality is that the illegal aspect of the operations of chainsaw loggers represent only about 5%of their operational costs.

The large concessionaires point to what they say is the waste of wood and unsustainable practices that result from chainsaw logging. A DFID-funded FRP Chainsaw logging Conversion Study carried out in January / February, 2006 -using a majority of one -inch thick material and some two-inch thick material at three different geographical sites - found that the average "merchantable" recovery for chainsaws was 44.4% while the average "merchantable" recovery from some of the most modern sawmills was 35.5%. Who, then, is really wasting wood?

The real reason why chainsaws produce lumber at such a low cost is simple - It takes the means of production to the tree rather than the tree to the means of production.

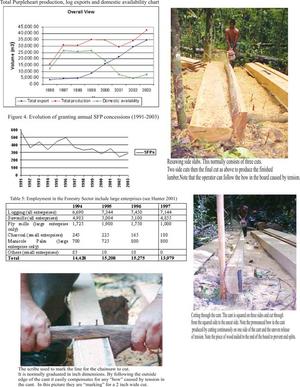

It is the role of chainsaw logging in supporting rural communities in Guyana that is, however, the real story. While the conventional logging/milling sector has been the recipient of substantial concessionary financing over the years our intrepid chainsaw operators have been vilified, harassed and treated with contempt. The fact is, however, that chainsaw operators actually pay their way. A study conducted by the Guyana Forestry Commission (GFC) in 2001/ 2002 found that chainsaw operators were paying almost half of the royalties being received by the GFC despite the fact that it occupies less than ÂĽ of the allocated forested lands. It should be added that chainsaw loggers "work" the worst, most denuded lands and that land being the worst and most denuded lands, already worked over by loggers and large concessionaires.

What is even more important than their contribution to the state coffers is their contribution to rural livelihoods. The aforementioned DFID/FRP Study found that, at a minimum, 70% of the money secured from sales made by chainsaw loggers returns to the communities. This figure is believed to have amounted to as much as $1 billion last year. Chainsaw logging also employs 75 per cent of the workers in the forestry sector.

During the nascent years of Precision Woodworking Ltd and in the wake of refusal by traditional millers to supply wood to certain manufacturers. it was the chainsaw sector that stepped in to fill the void.

Unfortunately, the much sought after Locust species exists only in limited quantifies on the concessions operated by chainsaw loggers hence their importation of this species from Brazil. When Bulkan Timberworks Inc. raised concerns about log exports in 2003 the milling sector immediately cut off its supply of Purpleheart. Again, the chainsaw loggers came to the rescue. Today, 70 % of all local lumber is supplied by the chainsaw operators. All of Bulkan Timberworks' supplies are provided by the chainsaw sector.

It is the chainsaw sector that has been the backbone of the manufacturing industry. It kept the manufacturing sector since the massive increase in log exports at the expense of local, value -added consumption left the manufacturing sector operating at 50% of capacity. In 2005, for example, Purpleheart constituted 42 % of all sawn and dressed lumber exports. Purpleheart is one of the most-used species by local manufacturers and that gap has been filled by chainsaw loggers.

There are two hundred and thirty state forest permits in Guyana today. Of these, four expatriate companies - through the expedient of subletting, in breach of article 13 of the Guyana Forest Act of 1953 - control more than 52% of the allocated state forests, and, more importantly, 69% of the prime concessions. In effect, and notwithstanding the valuable role that they continue to play in the Guyana economy, the significance of the chainsaw logger is being continually downplayed vis-Ă -vis the large operator whose proven intent is the wholesale export of prime species.

Significantly, chainsaw loggers appear to be the only operators in the forestry sector willing to embrace change and new technology. The large concessionaires have either closed down their mills for the short term expedient of increasing log exports or have assumed a posture that suggests an unwillingness to embrace portable technology. The portable sawmill is, in reality, a more efficient and effective chainsaw, providing higher recovery and better quality lumber.

What is needed in the timber industry is the movement of processing closer to the stump - so to speak - and to add as much "in country" value as possible thereby ensuring increased employment, greater revenue generation and skills transfer. In the case of the chainsaw operator vs the large logger, bigger is not better.

A more than eminent case has long existed for according the chainsaw sector greater recognition through an equitable redistribution of forest lands. For example, lands that are being held under illegal sub-let arrangements should be retrieved and redistributed. Instead, the number of chainsaw portable mill operators have continued to decline despite their obvious contribution to the sector and the economy as a whole and their desire to enhance the efficiency of their operations.

Internationally, it has long been recognized that the chainsaw operator is a legitimate part of the logging industry and that chainsaw logging is as a valid method of harvesting forest resources as any other particularly when account is taken of its considerable contribution to state revenue and rural livelihoods.

FRP - Chainsaw logging Conversion study 2006

FRP - Chainsaw Logging Marketing study 2006

LTS - Iwokrama timber harvesting study 2001

Member GMSA Wood Sector Group.

IPED - Youth Entrepeneurship Mentorship scheme